Microbe Talk - Invisible Friends

Posted on March 31, 2023 by Clare Baker and Jake M. Robinson

In our latest podcast, Clare and Microbiology Society member Jake Robinson discuss his new book Invisible Friends, the role of popular science books and how microbes can shape our lives and the world around us.

Music: That Science Ambient by ComaStudio on pixabay.

Read on for Jake's blog which takes us behind the scenes of the process of writing his book.

“Everything you can see in nature intimately depends on everything you cannot see.”

Invisible Friends is all about countering the prevailing narrative of microbes as the bane of society while providing much-needed clarity on their overwhelmingly beneficial roles. This was my core goal. Microbes such as bacteria, viruses, algae and others influence all aspects of our lives and the ecosystems that support all other life on Earth. Invisible Friends introduces the reader to a vast, pullulating cohort of minute life – friends you never knew you had! I discuss how microbes are vital for training the immune system, how they are the glue that holds our ecosystems together, and even how they influence decision-making… the way we think about how we think may need to be revisited! I also discuss how microbes are now considered in architecture and forensics and why they are a facet of social equity. The book is aimed to be of interest to a full spectrum of readers, from the general public to clinicians to researchers.

I began writing Invisible Friends in the final year of my PhD at the University of Sheffield, UK. The book is a concoction of science, journalism and personal memoir. Luckily, when it came to the science and personal memoir elements, I could free two birds with one key. Essentially, I wrote about my practical research experiences in microbial ecology. During my studies, I realised that ideas and knowledge are subject to evolution and flourishing, just like the microbes, plants and animals in a tangible ecosystem. Moreover, collaborations can trigger a form of nested symbiosis of thoughts––an ‘ecology of mind’. I was fortunate to collaborate with a diverse community of international researchers on my PhD journey, and reaching out to as many people as possible is something I highly recommend to new PhD students. These collaborations helped me generate a bounty of ideas for the chapters of Invisible Friends.

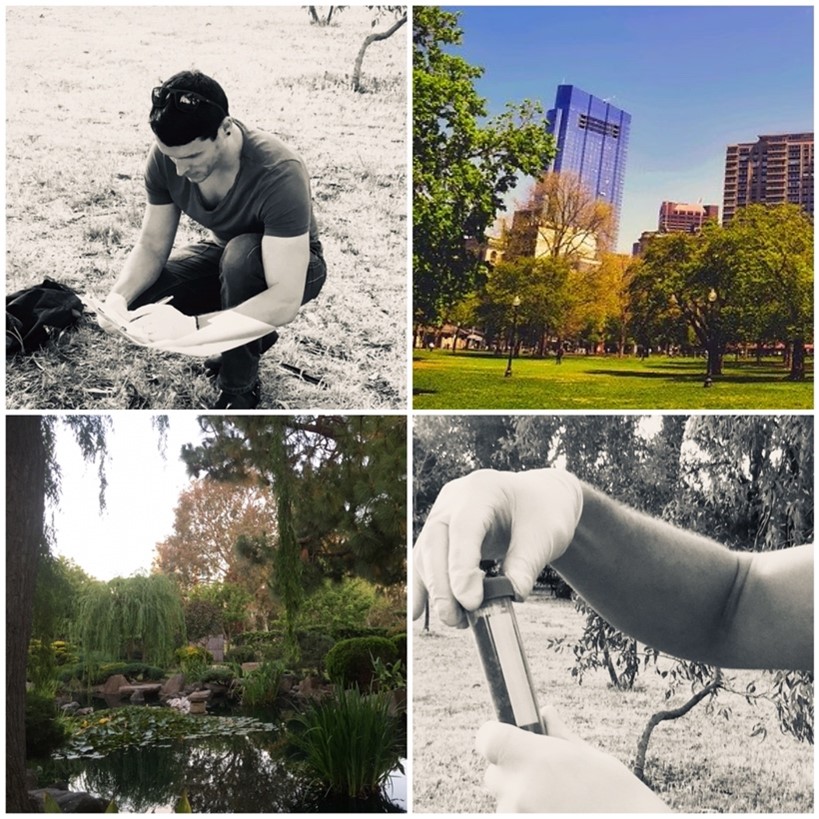

Me taking field samples for an ‘aerobiome’ study

Me taking field samples for an ‘aerobiome’ study

In addition to experiments and conversations with other humans, much of my ecological knowledge, and the ideas and inspiration born out of this knowledge, is gleaned by directly observing nature; it’s gifted by other ‘non-human’ organisms, some large (e.g., trees) and some invisible (e.g., bacteria and microscopic fungi), but all are equally potent educators. I wanted this notion of learning from and being inspired by nature to be conveyed in the book. And in fact, I spent many days sitting in woodland or on top of a cliff with my laptop, camping chair and a flask of tea, writing away. There’s something special about being in nature, away from the hustle and bustle, whilst writing about it––even if most of the nature I wrote about is the kind you cannot see! Here’s an excerpt from Invisible Friends, written whilst sitting in a peaceful woodland:

‘The forest is a beacon of serenity. The ground beneath my feet is carpeted with the creeping shamrock-shaped leaves of the edible wood sorrel. The air is rich with buzzing hoverflies, shield bugs and ladybirds. My eyes drift left, right, up and down across the trees’ diverse contours, textures and pleasing fractal patterns. I find myself considering the rich bounty of ecological niches and elegant adaptations surrounding me. And how each individual from the consortium of plants and animals I see with the naked eye is a diverse conglomerate of many organisms, the vast majority of which I cannot perceive. The trees are host to trillions of microbes. The trees need microbes for development, communication and, ultimately, their survival. The mosses that creep across the boulders are also home to trillions of microbes, as are the wood sorrel and the hoverflies and my solitary self. But this means I am, in fact, anything but alone. My body is a hive of activity, a bustling jungle full of life. I sit here emitting my personal signature in the form of a microbial cloud, and I bathe in the microbial clouds of the plants and animals around me. Our microbiomes are in constant flux and constant communication.’

The journalism part of the equation was far trickier for me. I had to learn how to interview people rapidly, ask the most pertinent questions, coax out the juicy details and inject life into the transcripts. In other words, I had to learn how to tell a story! To improve my journalistic adroitness, I started writing blogs, talking to other scientists and building questionnaires and interviews into my PhD research. I would write about my experiences, even if I didn’t publish them. This eventually helped refine my story-telling skills and provided the foundations I needed to begin writing a book. Once I started the book, I’d try and write 500 words per day, without worrying about the quality initially, as this is known to cause ‘writer’s block’. Most writers’ first drafts don’t read elegantly, and the sooner this is accepted, the sooner the draft will be finished, and you can then work on making it shine!

In addition to my experiences studying the wonderful unseen world in the lab and the field, the book includes the thoughts of world-leading experts in microbial ecology, neuroscience, social equity, restoration ecology, immunology, psychology, architecture and forensics. This diverse range of disciplines indicates the unfathomable influence microbes have on our lives and the world around us.

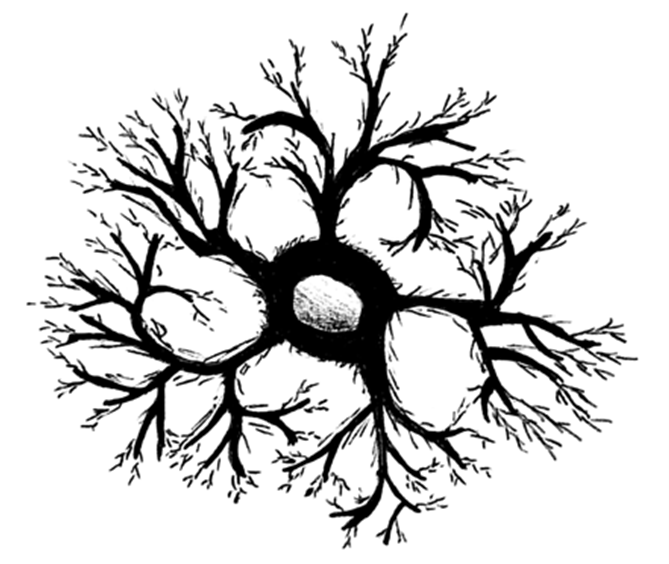

A microglial cell sketch from the book. These immune cells of the brain are critical players in connecting the microbiome, the immune system, and the brain. Sketching this made me pause for a moment and think how amazing it is that everything in life branches out, from tiny microglia and neurons to capillaries, tree roots and river deltas!

A microglial cell sketch from the book. These immune cells of the brain are critical players in connecting the microbiome, the immune system, and the brain. Sketching this made me pause for a moment and think how amazing it is that everything in life branches out, from tiny microglia and neurons to capillaries, tree roots and river deltas!

To order Jake’s Book visit Pelagic Publishing.

You can also keep up to date with Jake’s work here and on Twitter @_jake_robinson