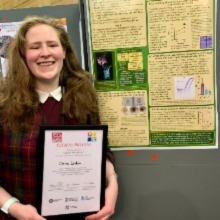

An interview with Claire Laxton

STEM for Britain is a scientific poster competition and exhibition organised annually by the Parliamentary & Scientific Committee in the Houses of Parliament. Posters from a variety of disciplines are presented at the exhibition with prizes awarded to those which best communicate high level science, engineering or mathematics to a lay audience. We approached Microbiology Society member Claire Laxton, who recently won the bronze medal in the ‘Biological and Biomedical Science’ section at STEM for Britain 2022, to share insight into her research and experience of presenting at this major event.

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your research?

I am a PhD student at the University of Nottingham, UK and I study a protein called AaaA which is a surface tethered peptidase on Pseudomonas aeruginosa and a vaccine target of interest because of its immunogenicity. I initially studied pharmacology as an undergraduate in Manchester, UK and then I did a placement in The Gambia. It was during my placement year, that ended up being very microbiology focused, that I realised that infectious disease surveillance and antimicrobial resistance were really interesting. On returning to complete my final year at university, I wanted to find something where I could combine my pharmacology degree with antimicrobial resistance and it so happened to be that a four year PhD programme in antimicrobial resistance had just launched at the University of Nottingham. I decided to jump onto that opportunity and that is how I got to where I am now.

What do you like the most about your work?

I like the fact that my project is quite broad in scope, which gives me the freedom to do quite a variety of things and get quite a broad set of skills from it. I spent the first part of my PhD doing structural work on AaaA, trying to model it and to purify it – unsuccessfully mostly as it’s a pretty tricky protein. Then I focused on figuring out what the protein does and I ended up working with the synthetic wound model as part of this.

How has your journey been so far – would you say you faced any challenges as an early career researcher?

I believe that the hardest thing about doing a PhD is finding the motivation to come in every day and do work when your performance is not always linked to clear goals and targets like in a ‘proper job’. You get out what you put in, and sometimes it is really hard to motivate yourself to put maximal effort in constantly and I definitely have learnt to ride the wave of motivation when it comes in peaks and troughs. When I am in a trough, I avoid doing big experiments unless I’m on a deadline, and focus on writing or other work instead, especially in my final year. This works for me, because I’ve learnt to trust that the peak will come around, and when it does, I’ll be able to pick up pace again.

What inspired you to enter the STEM for Britain poster competition?

A colleague at my institute sent out an email promoting it. It was a great public engagement opportunity and I have done public engagement before given my supervisor is involved in a lot of outreach work. For instance, we hosted a Royal Society handwashing exhibit a few years ago. This made me realise how much I enjoy public engagement and talking about science to non-scientific audiences.

What was your experience like presenting at the STEM for Britain poster competition?

None of the other scientists in the room were doing work which was remotely similar to what I was doing. For example, one person was studying how different exercise regimes could reduce back pain in astronauts. Another person was working on acoustics to track spider monkey conservation while the person across me was engineering strawberry flowers to be more attractive to bees to improve pollination. It made me realise how even across the sciences, we are not always accessible to each other. Even though the purpose of these kinds of events is to talk to the public, it was also a good chance for scientists to communicate with each other. This is going to be very important as we try to go forward because many scientific problems need multi-disciplinary solutions.

Why is it important to communicate microbiology research to policymakers and to the general public?

Most of the funding comes from them, and they make the decisions on where the funding goes in the future so they need to understand what we are doing and why it is important. I definitely also think that the pandemic has really highlighted how badly we need to have that open dialogue between scientists and non-scientists. We definitely need to do more to educate people and make science feel accessible, because if it doesn’t feel accessible then people switch off to it and you lose the chance to gain their trust.

It is also an important practice for us as scientists to bring our work out to the public and exercise communicating to someone else, so that we really understand what we are doing and where we are going with the impacts. In academia, it is often easy to follow your scientific curiosity and end up going off on random tangents that maybe are not as beneficial for your research in the long-term.

Why does microbiology matter?

The study of microbiology matters because there is a whole world that we cannot even see, that has a huge impact on literally every area of our lives; from helping us digest food to making sure soil has all the nutrients for our food to grow, to making us sick or even providing the solution to poor health. In fact, a lot of the technology we use for innovative medical research has often been borrowed from bacteria and viruses. If we do not study microbes, we do not get to learn from them and use this knowledge in a way that can help us to improve our lives.