Monkeypox

Monkeypox is caused by the monkeypox virus, a DNA virus similar to the virus which caused smallpox in humans. Find resources relating to the virus, its spread, symptoms and treatments below.

Ask A Microbiologist: What is monkeypox?

Q&A with Professor Neil Mabbott

With declared cases of monkeypox increasing in the UK and internationally, we spoke to Professor Neil Mabbott, Personal Chair of Immunopathology and Director of Teaching at the Roslin Institute, UK, and the The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies at the University of Edinburgh, UK. We asked him some common questions about monkeypox.

What is monkeypox?

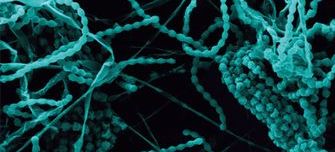

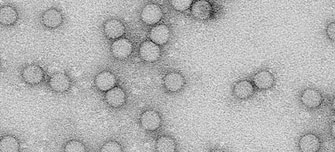

Monkeypox is caused by the monkeypox virus, a DNA virus similar to the virus which caused smallpox in humans. Monkeypox was originally identified in two groups of captive laboratory monkeys in the late 1950s. However, the virus also infects other animal species, especially rodents, squirrels and rabbits, in affected regions of sub-Saharan Africa.

-

Content from our journals

Read content from our journals about monkeypox, vaccines and other related topics.

-

On the Horizon: Monkeypox

Read more in our blog from 2017 about monkeypox and its relation to smallpox.

What are the symptoms of monkeypox and when should you seek advice?

The first symptoms of monkeypox usually develop within 5–21 days of infection. These include a fever, headache and muscle aches, swollen lymph nodes and tiredness. A few days after the onset of a fever, infected individuals can then develop a rash, usually starting on or around the face, and then this can spread to other parts of the body including the groin. The rash can then develop into characteristic pox blisters. Once these heal, the scabs will slough off and the person is then considered to no longer be infectious. Illness generally lasts from two to four weeks and individuals are infectious when the rash starts to develop, but sometimes people can be infectious from the onset of fever.

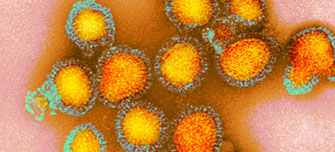

Is monkeypox like COVID-19?

No, the characteristic symptoms of monkeypox are quite distinct. COVID-19 is predominantly a respiratory disease, whereas monkeypox causes a blistering rash and respiratory disease is rare, but during the very early stages both can share some similar ‘flu-like’ symptoms. However, unlike COVID-19, infection with the monkeypox virus does not cause the loss of taste or smell or a persistent cough. Monkeypox is also less easily transmissible between humans than the coronavirus which causes COVID-19.

The viruses themselves are also different. The coronavirus that causes COVID-19 is a single-stranded RNA virus, whilst monkeypox is made of double-stranded DNA which means they infect their hosts very differently. RNA viruses like coronavirus also typically have a higher mutation rate than DNA viruses, and have traditionally been harder to make vaccines against, though of course we do now have very effective COVID vaccines.

How is the virus spread, and how easily transmissible is it?

The monkeypox virus is zoonotic; it can spread from an infected animal host to humans. Infections in humans can occur from close contact with infected animals or similar contact with infected humans, but fortunately the monkeypox virus doesn’t spread easily to humans, and very close contact is required for disease transmission.

The virus can infect the body through bites and scratches, broken skin (lesions), across mucous membranes (which are the wet body surfaces found in such places as the mouth and nose), via large respiratory droplets, bodily fluids, or via contact with infected materials such as infected bedding or clothing.

What are the current therapies/vaccines available?

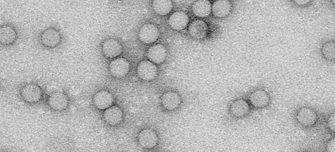

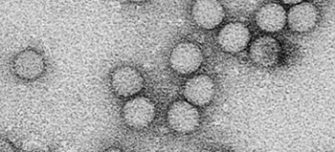

There isn’t currently a monkeypox-specific vaccine. However, since the smallpox and monkeypox viruses are closely related, smallpox vaccines are very effective against the monkeypox virus and have been used in the past in response to similar outbreaks.

Here in the UK, the Imvanex smallpox vaccine is being recommended for both pre- and post-exposure preventative treatment (prophylaxis) in infected patients, high-risk close contacts and health workers.

The vaccine uses a weakened or ‘attenuated’ version of the vaccinia virus Ankara strain as a vector. The vaccinia virus is closely related to the virus which causes smallpox, but as it is weakened in the vaccine it causes an immune response but is unable to cause disease or an infection in the body.

Find out more about variola major and variola minor - the viruses that cause smallpox - in 'Vaccinia Virus: a portrait of a poxvirus', the 2018 Marjory Stephenson Prize Lecture, presented by Professor Geoffrey Smith.

Imvanex is a third generation smallpox vaccine and uses a different vector from the original smallpox vaccine used in the past. Consequently, this vaccine has a good safety record and has been used in children without serious adverse reactions. It is considered safe to use in immunocompromised patients or those with underlying medical conditions after risk-assessment.

Certain antivirals have also been used to help treat patients with monkeypox and may provide some protection.

Find out more about vaccines in our video and podcast below.

Further resources

-

Vaccines: the global challenge for microbiology

Vaccines are made from microbes that are dead or inactive so that they are unable to cause disease. Not only do vaccines protect individuals, they can also provide herd immunity. We will explore four key areas of vaccination, including how vaccines work, are produced, more about herd immunity and eradicating disease.

-

Content from our journals

Read content from our journals about monkeypox, vaccines and other related topics.

-

Focus area: Vaccines

Read interviews with Society members who work in the field of vaccines, from those that help produce them, to those who are fighting to help eradicate diseases.

-

On the Horizon: Monkeypox

Read more in our blog from 2017 about monkeypox and its relation to smallpox.

-

Vaccines: From the cowshed to the clinic

In this 2016 blog post, we spoke to Dr Sarah Gilbert from the Jenner Institute about how vaccines work, how are they manufactured and what are the challenges involved, looking at the smallpox vaccine in particular.

-

Vaccines journals collection

This Vaccines collection brings together the work of our journals on current and future vaccines, how they protect not just humans but animals as well, and how they are created.

-

Vaccination

A vaccine is a substance that is introduced into the body to stimulate the body’s immune response. It is given to prevent an infectious disease from developing and the person becoming ill. Find out more.

Image credits:

Science Photo Library/Dennis Kunkel Microscopy

James Gathany/Public Domain

CDC/Science Photo Library

Cameron Baines

iStock/Panorama Images

Nicola Stonehouse and Oluwapelumi Adeyemi

Wellcome Collection under CC BY 4.0

iStock/Samara Heisz

CDC/Cynthia S. Goldsmith, Russell Regnery