Polio

Polio, or poliomyelitis, is an infectious disease caused by poliovirus. Find resources relating to the virus, its spread, symptoms and prevention below.

Ask a microbiologist: What is polio?

Q&A with Professor Nicola Stonehouse

The virus that causes polio has been detected in a number of sewage samples in London, UK. We spoke to Professor Nicola Stonehouse, a Professor in Molecular Virology at the University of Leeds, UK, to ask some common questions about polio and why the virus has been making headlines in recent weeks.

What is polio and how does it spread?

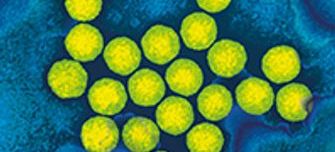

Polio is caused by a small RNA virus called poliovirus. There are three types of polio: type 1, type 2 and type 3. The virus predominantly infects children and it spreads very easily by what we call the faecal-oral route. This could be through contaminated water, sewage or person-to-person contact.

-

Content from our journals

Read content from our journals about polio and other related topics.

-

Polio policy briefing

Read our policy briefing from 2013 about the history of polio eradication and search for future vaccines.

What are the symptoms of polio?

For most people who get polio, it causes similar symptoms to the common cold and can cause some stomach upset. But it usually doesn’t cause many problems. It is only in a small number of people where polio moves to the nerves, instead of staying in the gut where it normally sets up an infection. This can cause temporary or permanent paralysis and, in some cases, death. Before we had vaccines, polio was the primary cause of disability worldwide.

What polio vaccines are currently available?

There are two main types of polio vaccine: a live attenuated vaccine given orally and an inactivated vaccine given by injection. We use the inactivated vaccine in the UK and throughout the majority of the world.

The oral polio vaccine has a problem as people can sometimes shed viral material from the vaccine in their stools. This can result in ‘vaccine-derived polio’, which can spread to others. However, this is not an issue if everybody is vaccinated against polio.

It is common for babies and young children to shed for a day or two post-vaccination. But, very rarely, as the virus has a high mutation rate, the attenuated virus can regain virulence. If this is shed, then this ‘vaccine-derived poliovirus’ can cause disease in others too.

-

Using yeast to produce a better polio vaccine

Explore how researchers are using yeast to produce virus-free virus-like particles to make the next generation of polio vaccines safer in a post-eradication world.

-

An interview with Dr Lee Sherry

Read this interview with Microbiology Society Champion Dr Lee Sherry and discover how his research on new polio vaccines is helping to eradicate the disease.

-

An interview with Professor Jeffrey Almond

Read this interview with Microbiology Society member Professor Jeffrey Almond and learn more about how his research contributed to the understanding of poliovirus.

How big of a problem is polio across the world?

Wild polio is an ever-decreasing problem. Polio types 2 and 3 are considered by the World Health Organisation to be eradicated in the wild and there are now only two countries in the world where wild polio is endemic: Pakistan and Afghanistan.

However, we can still get outbreaks for two reasons. Migration of people can result in outbreaks of wild polio, and we can also get outbreaks of vaccine-derived polio in areas where there is low vaccine coverage.

-

Hot topic lecture: Paralytic disease caused by enteroviruses: the role of non-polio serotypes

At the Microbiology Society's 2019 Annual Conference, Dr Javier Martin (National Institute for Biological Standards and Control, UK) gave a Hot Topic lecture on the upsurge of reports of a ‘polio-like’ disease in the UK in 2018.

-

Polio – what are the prospects for eradication?

Learn more about the prospects for worldwide polio eradication in this Microbiology Today article from the 2017 issue on 'Halting Epidemics'.

Why are we hearing about polio in the news at the moment?

For many years, surveillance has been carried out in sewage within the UK and across the world looking for many different viruses, including polio. It is not uncommon to find polio in sewage and for this to have come from the oral vaccine.

In London, we found samples of polio type 2 that is vaccine-derived. But when we look at the genetic sequence of the virus, we don’t just see one sequence, we see multiple. Because of the range of different sequences being reported, it looks like there is transmission. We have vaccine-derived polio type 2 spreading in the population, and that is worrying.

This has probably come from somebody who has had the oral polio vaccine and is shedding it. They may not know that they’re shedding and they may be a visitor to the UK. The virus is therefore spreading to unvaccinated or poorly vaccinated individuals.

What is your advice to people who are worried about the spread of polio in the UK?

For the majority of people who are fully vaccinated against polio, it doesn’t pose much risk. The polio vaccines are incredibly effective, so if you are fully vaccinated against polio, you will be protected. But for very young children and children who may have missed their vaccines over the last couple of years, those neurological symptoms can be a warning sign and parents should seek medical advice.

If you think that members of your family have not been fully vaccinated or if you’re unsure, now would be a good time to get a booster. An extra vaccine shot will not do any harm, so it’s better to be safe than sorry.

Find out more about the upsurge of polio-like paralytic disease reported a few years ago in 'Paralytic disease caused by enteroviruses: the role of non-polio serotypes', a 2019 Hot Topic lecture presented by Dr Javier Martin.

Find out more about vaccines in our video and podcast below.

Further resources

-

Vaccines: the global challenge for microbiology

Vaccines are made from microbes that are dead or inactive so that they are unable to cause disease. Not only do vaccines protect individuals, they can also provide herd immunity. We will explore four key areas of vaccination, including how vaccines work, are produced, more about herd immunity and eradicating disease.

-

Focus area: Vaccines

Read interviews with Society members who work in the field of vaccines, from those that help produce them, to those who are fighting to help eradicate diseases.

-

Vaccines journals collection

This Vaccines collection brings together the work of our journals on current and future vaccines, how they protect not just humans but animals as well, and how they are created.

-

Vaccination

A vaccine is a substance that is introduced into the body to stimulate the body’s immune response. It is given to prevent an infectious disease from developing and the person becoming ill. Find out more.

Image credits:

iStock/selvanegra

Shutterstock/Creations

iStock/Dr_Microbe

Lee Sherry

Jeffrey Almond

Microbiology Society

Science Photo Library/Dr Linda Stannard UCT