Life after a pandemic: What we can learn from the Spanish flu?

Posted on July 30, 2020 by Fiona Mitchell

With the slow return to a new ‘normality’, it is hard to know what life will be like out of lockdown. A direct comparison to the current situation with SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) is the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918. Spanish flu affected a staggering one-third of the world’s population and killed 50 million. As much as the two viruses are very different, the societal reactions during both pandemics are similar, and our way of coping with COVID-19 can be understood by reflecting on the measures used 100 years ago.

Red Cross staff help to transport a Spanish flu victim, Missouri, 1918

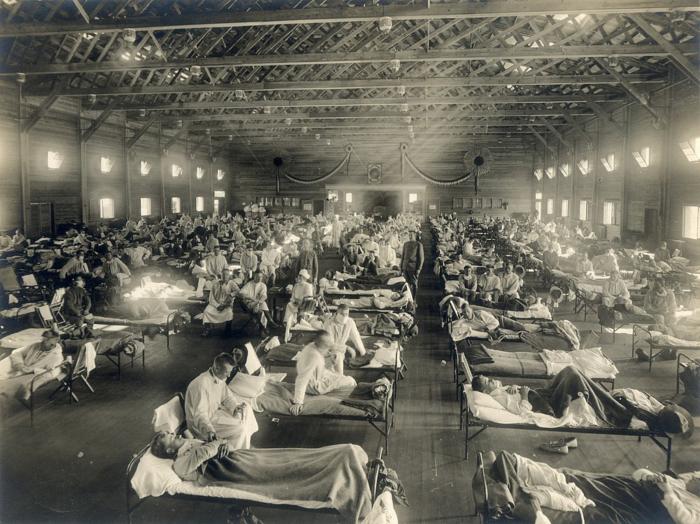

In March of 1918, a mysterious illness was detected amongst soldiers in a Kansas army base. Soldiers at Fort Riley were suddenly dying from a flu-like disease, but due to wartime restrictions, this outbreak and others around the world were not widely reported in the press. As Spain was neutral, these restrictions did not apply, so when King Alfonso XIII became gravely ill in April 1918, the news spread, which gave the impression that Spain was the most affected country.

Fort Riley, Kansas where the flu outbreak began, 1918

The flu was first noted in Britain in May 1918 - supposedly arriving through the Port of Glasgow - and by June it was in London. As in the USA, the British press had difficulties reporting the seemingly irreverent flu outbreak while war was still raging on the continent. As a result, many people were unaware of the virus and only localised precautions were made.

Conversely, in the present day, we are instantly able to access the latest available data on the COVID-19 pandemic from infection rates, daily death toll or government advice. Our current understanding of viruses is beyond the comprehension of even the top scientist of 1918, having only been discovered at the end of the 19th century, public health was in its infancy and epidemiology was non-existent. This helps to explain why the worldwide spread was so fast and why exact figures on those affected are unknown.

Traffic Warden in New York, 1918

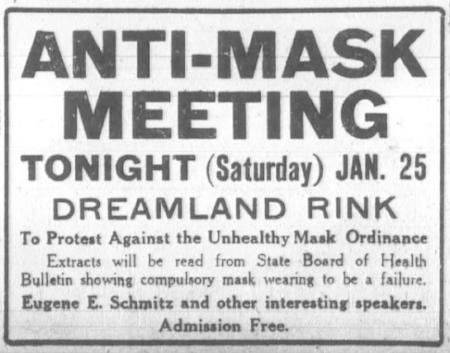

A phrase many of us would not have come across until March this year is ‘social distancing’ in which we have been encouraged or in some cases forced to keep away from other people. This was also used in 1918, with a comparable response to now, as many schools closed and public events were cancelled. Cheltenham Boys School did the reverse by locking the pupils and staff inside the school building. Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, a measure introduced to reduce contact in the most populated city included the staggering of rush hour by New York city’s health commissioner Dr Copeland. Restricting what people can do is always hotly debated, and the recent debate in the press on the need to wear masks while in public spaces and on public transport is not a modern concern. Historian Samuel Cohen has referred to the ‘anti-mask league’ of San Francisco in early 1919, which gained backing from several thousand people opposed to wearing a mask.

From the San Francisco Chronical, 25th January 1919

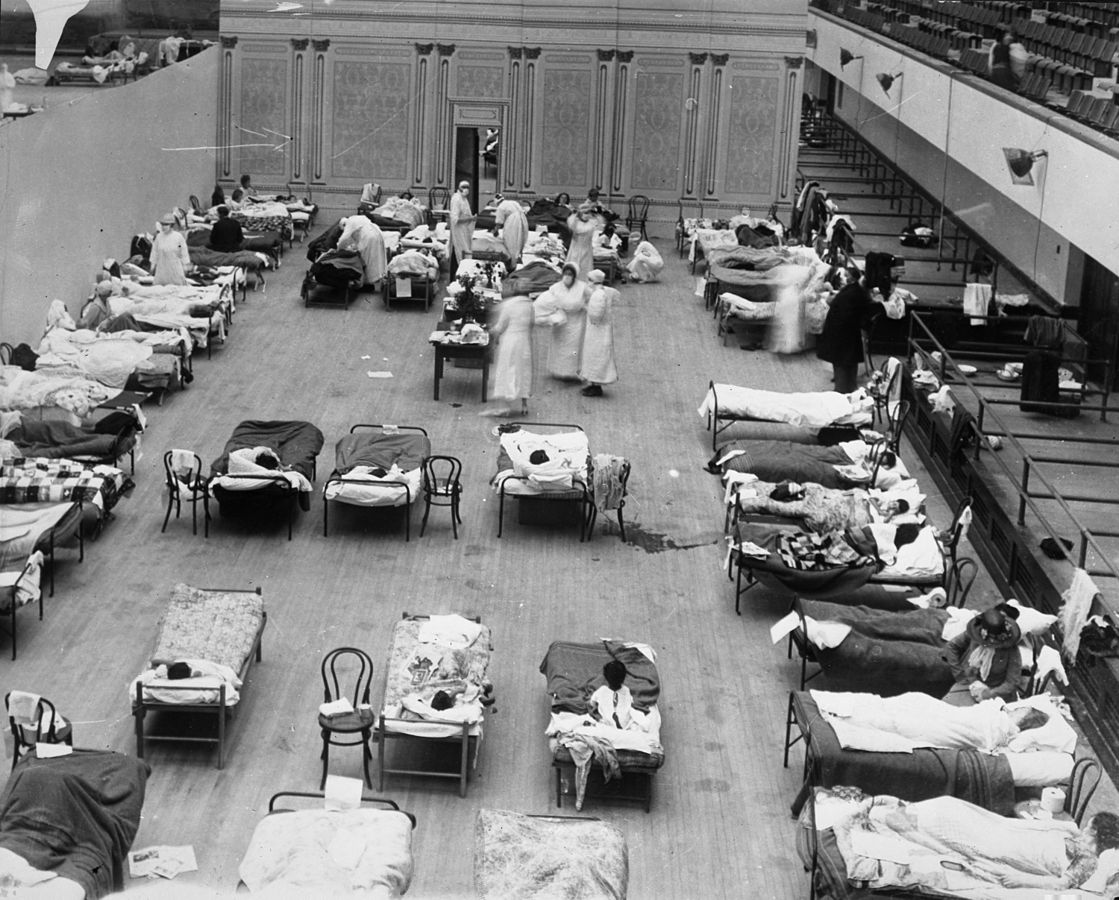

An early reason for the social restrictions in Britain was to protect the NHS from being overwhelmed by cases. In March 2020, we saw the government rush to build additional medical facilities throughout the country to help the crowded hospitals cope with the influx of impending cases. In 1918, the country was dealing with the devastation of war and the greatest loss of lives in any conflict. The UK was not prepared for a pandemic, with many doctors, nurses and medical supplies still on the battlefields of France and Belgium. The post-war movement of troops and medics across the globe has been considered one of the main reasons the Spanish flu spread so quickly. Earlier this year, we became aware of the lack of personal protective equipment for medical staff, which led for a national push to help facilitate this – another scenario paralleled in 1918.

Oakland Auditorium used as a temporary hospital in 1918 compared with the Los Angeles Convention Center prepared for COVID-19 patients:

The Spanish flu virus was persistent and wiped out a huge proportion of the globe during its deadliest second wave in the autumn of 1918. A third wave came in the winter of 1919, however by summer of that year, very few cases were reported. Science journalist Laura Spinney has fervently researched the Spanish flu and analysed how it was concluded. She reasons that every pandemic is shaped like a bell curve as the pathogen runs out of susceptible hosts, therefore the Spanish flu ran its natural course. There could be a similar pattern for the current pandemic.

So, what have we learnt from the 1918 pandemic? That preventative measures - however difficult and limiting - do make a difference in slowing the spread of disease. That no matter how developed a health care system can be, there will still be problems. Yet positively, we can see that pandemics do all come to an end. As 100 years ago, the nation basked in a euphoric ‘roaring’ 20s, we too will experience our own roaring 2020s.